Texas Judge Issues Preliminary Nationwide Injunction Against Corporate Transparency Act

On December 3, 2024, Judge Amos L. Mazzant III of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas issued a nationwide preliminary injunction in the case of Texas Top Cop Shop, Inc. et al. v. Garland, halting the enforcement of the Corporate Transparency Act (the "CTA") and its reporting obligations. This ruling could significantly affect millions of businesses across the United States.

Case Summary

The plaintiffs, led by Texas Top Cop Shop, Inc. (a family-run firearms and tactical gear retailer) along with the Libertarian Party of Mississippi and the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), challenged the constitutionality of the CTA. Among other things, the plaintiffs argued that implementing and enforcing the CTA (and its reporting obligations) exceeds Congress’ authority under the Commerce Clause. They also contended that the provisions of the CTA:

- intrude upon states’ rights under the Ninth and Tenth Amendments;

- compel speech and violates First Amendment rights of association; and

- violate the Fourth Amendment by requiring disclosure of private information without individualized suspicion or judicial process.

While not ruling on any of the above arguments specifically, Judge Mazzant found that the plaintiffs satisfied all prerequisites for obtaining a preliminary injunction (including finding a substantial likelihood of success on the merits of their claims). As a result, the court granted the requested preliminary injunction, enjoining enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations) and staying the January 1, 2025 CTA reporting deadline. Moreover, the court clarified that the granted preliminary injunction is intended to apply nationwide.

Court’s Jurisdiction to Enjoin the CTA

As the primary basis for its power to issue a nationwide injunction, the court cites "the judicial power of the United States" under Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part:

"That power is not limited to the district wherein the [C]ourt sits but extends across the country. It is not beyond the power of a court, in the appropriate circumstances, to issue a nationwide injunction."[1]

The court further added that under section 705 of the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. 705), "the reviewing court" may "issue all necessary and appropriate process to postpone the effective date of an agency action or to preserve the status or rights pending conclusion of the review proceedings" to "the extent necessary to prevent irreparable injury." The court also noted that the foregoing power has been interpreted as being akin to a preliminary injunction.[2]

While federal district courts have certain authority to issue injunctions outside of the immediate district, the scope of this particular ruling is unusually broad. The court justified its nationwide approach by stating that "a nationwide injunction is appropriate in this case" because the CTA (and its reporting obligations) apply nationwide and because the NFIB’s membership extends across the country. Accordingly, per the court, it cannot provide the plaintiffs with "meaningful relief without, in effect, enjoining the CTA [(and its reporting obligations)] nationwide."

In recent years, nationwide injunctions have become the subject of serious debate.[3] The U.S. Supreme Court has expressed concerns about nationwide injunctions issued by district courts. Critics argue such injunctions exceed the issuing court’s authority and circumvent the normal appellate process.

As noted by the court here, another concern is that "nationwide injunctions curtail the percolation of legal debate among lower courts." As argued by the defendants in this case, this concern specifically relates to the recent Alabama case[4] (the "Alabama CTA Case"), where the court is already considering the constitutionality of the CTA (and its reporting obligations). For these and other reasons, there is a significant chance that the scope of this injunction may be challenged and ultimately changed.

Court’s Jurisdiction to Enjoin the CTA

Assuming the preliminary injunction in this case is challenged, it could face a significant risk of reversal on appeal. Among other things, the government can, and most likely will, argue one or more of the following:

- National security and law enforcement interests: The government will likely emphasize the CTA’s importance in combating money laundering, terrorism financing, and other financial crimes.

- Broad regulatory authority: Courts have historically granted Congress (and federal agencies) wide latitude (including in regulating economic activity under the Commerce Clause).

- Limited precedent: This case presents novel issues regarding the constitutionality of beneficial ownership reporting requirements. Appellate courts may be reluctant to uphold such a sweeping injunction without more developed case law.

- Narrow tailoring: The government may argue that the CTA’s reporting requirements are sufficiently narrow and include adequate privacy protections to withstand constitutional scrutiny.

Comparison to Alabama CTA Case

This case draws certain parallels to the Alabama CTA case, including arguing that:

- the implementation and enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations) exceeds Congress’ authority;[5] and

- the CTA (and its reporting obligations) are unconstitutional.

However, there are two distinct differences between this case and the Alabama CTA Case:

- First, in the Alabama CTA case, the court actually found that the CTA (and its reporting obligations) were unconstitutional and that Congress had exceeded its authority in implementing and attempting to enforce the same. This contrasts with the current action where the court made it expressly clear that it was not making an affirmative ruling on such claims.

- Second, the injunction provided by the court in the Alabama CTA case enjoined the enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations) solely against the named plaintiffs. This is in contrast to the court's current action, which is attempting to enjoin enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations) nationwide and for all.

Conclusion

The U.S. government has sixty days to appeal the decision in this case and seek a reversal of the preliminary injunction. The losing party could then seek review in the U.S. Supreme Court. In addition, it is highly likely that the validity of the CTA will be revisited in a district court in another circuit (most likely the District of Columbia), which could present a conflicting decision.

The decision in this case (and any potential appeals of that decision) has far-reaching implications for the enforcement of the CTA and the regulatory landscape for small businesses. Entities impacted by the CTA should monitor this case closely and seek professional advice to navigate these evolving legal developments.

That being said, no matter the outcome, the process will not be completed before the December 31, 2024 CTA filing deadline. Moreover, if the injunction in this case is eventually overturned, it is unclear what penalties could or would be imposed for those who failed to file by the December 31, 2024 CTA filing deadline.

The CTA already provides for significant penalties for non-compliance (a fine of $591 per day and up to two years in prison). For these reasons, it is recommended that those subject to the CTA reporting requirements prepare to make their required filings by the December 31, 2024, filing deadline. In the interim, we will continue providing insights and updates on developments in this case and any other actions that attempt to challenge the CTA.

* December 9, 2024 Update

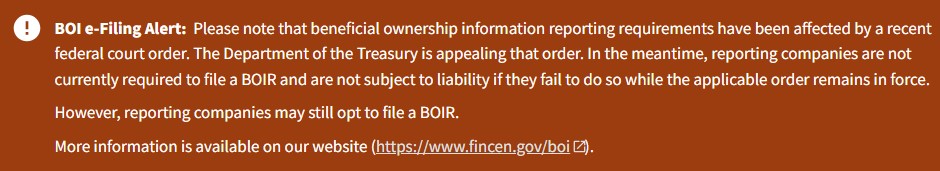

Shortly after the release of this alert, FinCEN posted the following notice to its CTA reporting portal:

As part of the “more information” noted above, FinCEN also stated that “[t]he government continues to believe—consistent with the conclusions of the U.S. District Courts for the Eastern District of Virginia and the District of Oregon—that the CTA is constitutional.”

The above definitively confirms that FinCEN’s enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations) has been put on an indefinite hold. However, as noted above, there is a significant likelihood that the current injunction will be overturned or otherwise significantly scaled back. While the current injunction stays the enforcement of the CTA (and its reporting obligations), in the event the injunction is overturned or scaled back, there is no way of knowing how much additional time (if any) FinCEN would provide for companies to satisfy their reporting obligations which may leave many scrambling to report or face the harsh penalties.

Accordingly, our recommendation remains generally the same as noted in our Conclusion above. Those subject to the CTA reporting requirements should monitor FinCEN’s appeal of this case closely and be prepared to make their required filings quickly should the ruling be overturned or otherwise modified. In the alternative, they can file their CTA reports voluntarily by the original December 31, 2024 or other applicable deadline.

[1] Citing also: Texas v. United States, 809 F.3d 134, 188 (5th Cir. 2015) (upholding nationwide injunction in immigration context) (citing Earth Island v. Ruthenbeck, 490 F.3d 687, 699 (9th Cir. 2006) (upholding nationwide injunction after concluding it was “compelled” by the text of Section 706 of the APA), aff’d in part and rev’d on other grounds by Summers v. Earth Island Inst., 555 U.S. 488 (2009); Chevron Chem. Co. v. Voluntary Purchasing Grps., 659 F.2d 695, 705–06 (5th Cir. 1981) (instructing district court to enter nationwide injunction); Hodgson v. First Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n, 455 F.2d 818, 826 (5th Cir. 1972) (“[C]ourts should not be loathed to issue injunctions of general applicability . . . ʻthe injunctive processes are a means of effective general compliance with national policy as expressed by Congress, a public policy judges must too carry out—actuated by the spirit of the law and not begrudgingly as if it were a newly imposed fiat of a presidium’” (quoting Mitchell v. Pidcock, 299 F.3d 281, 287 (5th Cir. 1962

[2] Citing Wages & White Lion Invs., L.L.C., 16 F.4th at 1135 (citing Nken, 556 U.S. at 426).

[3] See, e.g., Texas v. United States, 515 F. Supp. 3d 627, 637–38 (S.D. Tex. 2021) (collecting authority on both sides).

[4] NSBU v. Yellen, No. 24-10736 (11th Cir.).

[5] It should be noted that under the Alabama CTA Case the court focused on the CTA (and its reporting obligations) exceeding Congress’ authority under Article I of the U.S. Constitution, as opposed to its authority under the Commerce Clause which is argued in this action.